Two Ways to Ensure That Philanthropic Funding Is Money Well Spent

Philanthropy and the nonprofit sector have seen several evolutionary changes over the past decade. We look at two important developments – listening to the needs of beneficiaries and respecting grantee organizations – in the second edition of Money Well Spent.

“Listening to Those Who Matter Most, the Beneficiaries,” the 2013 SSIR article by Fay Twersky, Phil Buchanan, and Valerie Threlfall, highlighted “beneficiary voice” as a critical way to ensure that philanthropic strategies are truly responsive to the needs of their intended beneficiaries. At the same time, the techniques of “human centered design” emerged in response to the basic insight that, whether you are designing consumer products or social interventions, you must immerse yourself in the lives of your customers or beneficiaries to understand their motivations, needs, and behaviors.

Also around the same time, in an article titled “Beyond the Veneer of Strategic Philanthropy,” Patricia Patrizi and Elizabeth Thompson argued that “grantees need to be treated as the central partners that they ultimately are in the strategy process. They are not only the main executors of strategy, but have the on-the-ground knowledge and experience essential to sort the wheat from chaff in strategic thinking.”

Although these points may seem obvious, many philanthropists seem oblivious to them. In developing strategies, they don’t consult with grantees, let alone their mutual beneficiaries. Rather, they often act as if wealth and good intentions suffice to develop successful interventions.

To nudge the field forward, two beneficiary voice authors have joined with partners to create a funder collaborative, The Fund for Shared Insight, with the goal of helping foundations and nonprofits connect to each other and to the people and communities they seek to help – and be more responsive to their input and feedback.

How grants are structured matters too. In Money Well Spent’s discussion of funder-grantee relationships, we emphasize the value of general operating support grants, and won’t repeat the arguments here. But we also note that it sometimes makes sense to support particular projects, and it’s no scandal to do so. What is a scandal is to provide project support without paying adequate overhead, or indirect costs.

Imagine hiring a plumber to unclog your drains. He submits a bill for $100, but you write him a check for only $75. When he asks about the other $25, you explain that you’re paying only for his direct costs–his time on the job and any materials used–and not for indirect costs such as maintaining his shop, advertising, insurance, and the like.

Outrageous behavior? Absolutely.

Yet many philanthropists and foundations treat their grantee organizations this way every day. And while you can be pretty sure that the plumber won’t work for you again, most grantees suck it up, skimping on vital systems and engaging in “creative” cost accounting, which increases funders’ skepticism about their actual costs.

What does overhead pay for? Expenses such as the classic back-office costs—rent, insurance, utility bills, and so forth. It also generally includes support staff, staff programs, and piloting new programs in new regions. In short, “overhead” is actually the backbone of running any organization. There are no doubt instances where overhead trips into waste: a good eye for financial statements followed by focused questions is the way to uncover those problems; a blanket policy is illusory, and often self-defeating, oversight.

So why would most philanthropists never cheat commercial vendors in this manner but routinely stiff their nonprofit grantees—while calling them “partners”—by refusing to pay full indirect costs? There are several possible explanations. While you will know whether the plumber unclogged your drains, it’s often harder to know whether you got what you paid for with a grant to a nonprofit organization. Donors may erroneously believe that a high overhead rate indicates low effectiveness. Also, in the absence of generally accepted cost accounting principles, donors may have greater confidence in an organization’s budget for direct costs.

Studies of the field reveals that even the most efficient and effective nonprofit organizations have a much higher indirect cost rate than the 10-15 percent maximum of many foundations—and some foundations pay no overhead at all. Recent research persuaded Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, to increase its standard overhead rate to 20 percent while working with others in the sector “to encourage more honest dialogue about the actual operating costs of nonprofit organizations.”

Needless to say, we hope that this effort succeeds. But we see at least two barriers that must be overcome. First, Charity Navigator, by far the most popular charity rating service, provides no information about an organization’s impact, but counts indirect costs against its rating. Second, efforts to persuade philanthropists to pay full indirect costs face strong psychological headwinds. In examining what they called “overhead aversion,” a team of social scientists concluded that donors “feel that they made a greater impact when they know they are helping the cause directly as opposed to when their contribution pays the salary of a charity’s staff member.”

Whether or not overhead aversion is psychologically explainable, it is not morally justified. It is parasitic on those funders who do provide general operating support (which includes indirect costs) and throws organizations into what has aptly been termed the “nonprofit starvation cycle.”

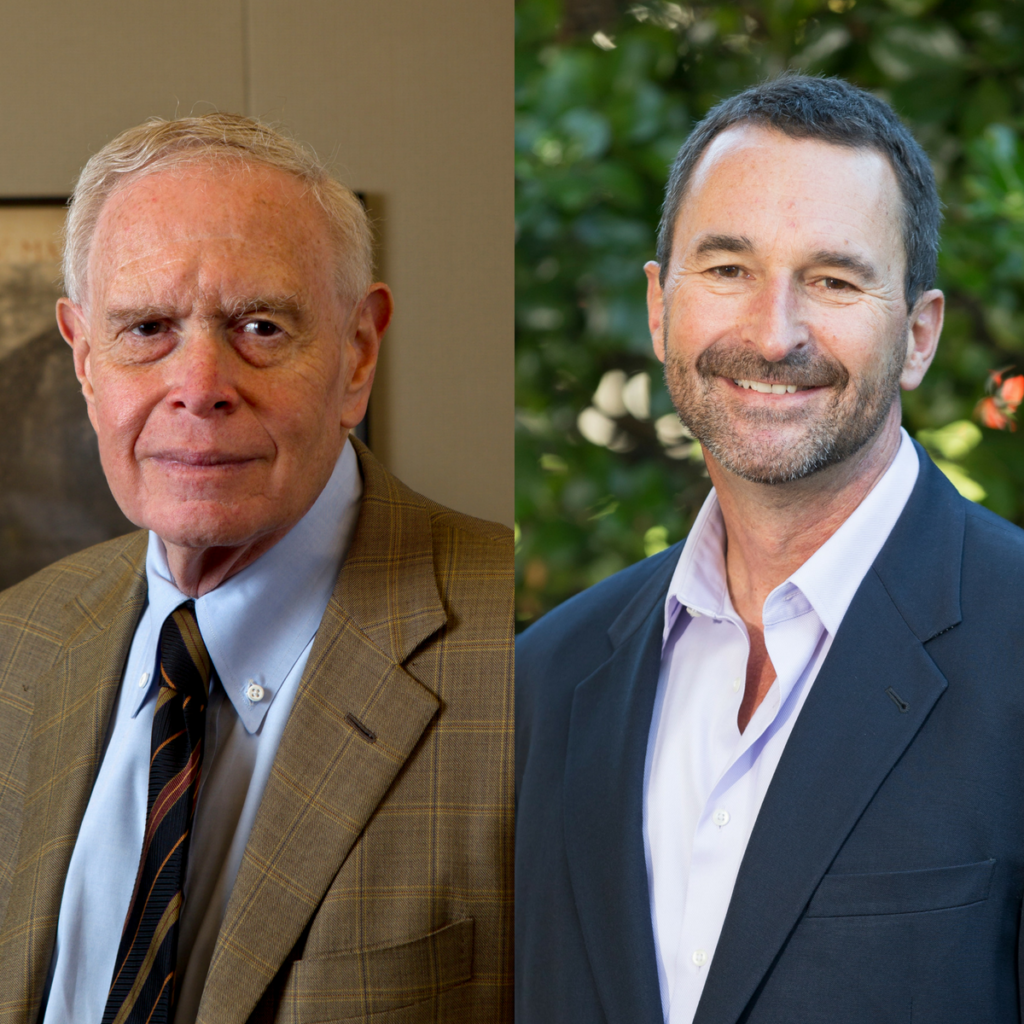

Paul Brest and Hal Harvey are the authors of Money Well Spent.

Paul Brest is Former Dean and Professor Emeritus at Stanford Law School, a Lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Business, Co-Director of the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society, and Co-Director of the Stanford Law and Policy Lab. He was President of the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation from 2000-2012.

Hal Harvey is the CEO of Energy Innovation, a San Francisco-based energy and environmental policy firm. Previously, he was founder and CEO of ClimateWorks Foundation, a network of foundations that promote polices to reduce the threat of climate change; Environment Program Director at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation; and founder and President of the Energy Foundation, a philanthropy supporting policy solutions that advance renewable energy and energy efficiency. He has also set up foundations in China, Europe, and India.